ECE's Kenneth L. Johnson featured in Crain's NY Article on Diversity Recruiting.

Can corporations that say they will become more inclusive to Blacks and Latinos be believed? - by Gwenn Everett

Even during the current public reckoning around race at top businesses, the old order of corporate New York might be hard to shake, experts warn.

That might be hard to imagine as vaunted companies, including The Wing, ABC and The New York Times , underwent high-profile personnel shakeups amid employee complaints of racial inequity. The biggest corporate names in the city—typically a politically cautious group—have condemned racism in droves and made multimillion-dollar donations to foundations.

Underlying those headlines of change, though, is another reality: Much of corporate New York is still treating diversity the way it has for years. Companies say that's because racial equity was a priority long before protests over George Floyd's killing by Minneapolis police rocked the country. But the companies where leadership changed this month had diversity initiatives in place, too.

Experts say the policies that corporations have enacted so far have produced sluggish progress—even from sectors that are otherwise experts in solving problems.

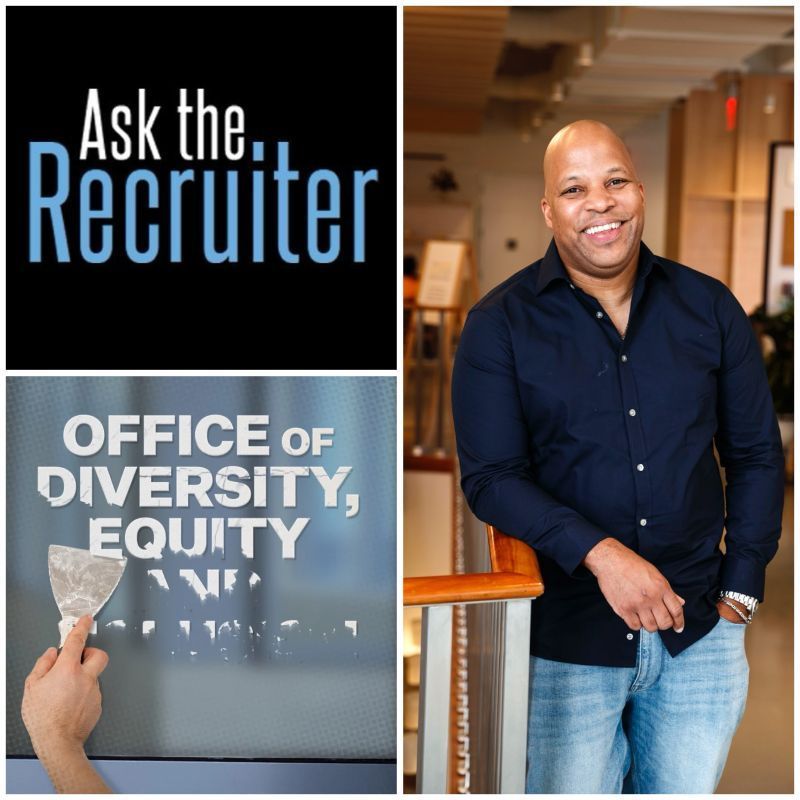

"We hear every year that this will be the year that companies pay more attention to diversity," said Kenneth Johnson, president of East Coast Executives, a recruitment firm in Harlem. Johnson consults with companies looking to hire more diverse candidates for senior roles.

When it comes to corporate gestures toward diversity, Johnson is wary.

"I've stayed away from kind of buying into those types of statements, because the follow-through has been horrendous," he said. "It's almost been nonexistent.”

Percentage change

It's a puzzling truth given that companies are not shy about setting, and publicizing, diversity goals. Citigroup said in January that 8% of its mid- and upper-level managers would be Black by the end of next year. Goldman Sachs promised last year that a quarter of its analysts and new associates would be Black or Latino hires. Nike, which unveiled new a Midtown headquarters and flagship store in 2017, pledged to hire more underrepresented groups for mid-level management roles in its last Impact Report, which measures diversity in its workforce.

But it's hard to see such corporate pledges as ambitious. Citigroup and Goldman both were aiming to hire a smaller percentage of Black people for their management and entry-level ranks than is in the population as a whole. The United States is about 12.7% Black. Goldman characterized its goal of 25% Black and Latino new associates and analysts as "aspirational," but together those segments make up about 31% of the U.S. population, according to the Census Bureau. Nike has not even set a hard benchmark for its midlevel management hiring.

Part of the issue is that structural forces distort the workforce before firms even begin hiring, said Jerry DeBerry, partner and director of diversity at law firm Mayer Brown, which has a location in Midtown.

"The percentage of Black people going to law school is certainly much lower than the percentage of Black people in the U.S.—significantly lower," DeBerry said. "And we know that as a firm, and as a profession."

The firm, whose associates are 36% people of color or LGBTQ, does outreach at the high school and college level to try to bolster the pipeline of potential Black lawyers.

The outreach has more than tripled the percentage of its partners who are people of color or otherwise diverse, to 16%, DeBerry said. But that's still a couple of percentage points below the industry standard.

"Companies have been engaged in diversity-enhancing practices for decades now. So many of the messages that you're hearing, they're not new," said Sean Rogers, professor of human resources and labor relations at the University of Rhode Island, where he is the business school's chief diversity officer. "The fact that many corporations have been talking about this for decades but we're still seeing problems," he added, "indicates that there is more talk than action."

The past month has shown that representation is not in itself a solution. At ABC News, The New York Times and The Wing, executives stepped down and were placed on leave amid complaints that company culture remained racially insensitive, regardless of the on-paper diversity the firms could boast.

In each case, the executive who stepped down was white and managed a workforce with people of color who complained of insensitivity at best, and toxicity at worst, in their firm's decision-making.

"There's a big difference," DeBerry said, "between being diverse and inclusive."

The New York Times declined to comment. In messages to their staffs, The Wing and ABC News said they were taking the events of recent weeks seriously. ABC launched an investigation into its executive placed on leave. The Wing said it was taking time to reflect.

Companies have not put many people of color into management roles, Johnson said . At Nike, more than one-fifth of its workforce is Black, but only 4.8% of its directors are.

"There's no system in place to sponsor these employees to get them onto leadership paths," Johnson said. "Then they get into a track of job jumping, but it's basically because they never found a job that supported their job journey."

That's not to say that firms have not made any progress. Goldman has met its goal of 25% Black and Latino analysts, and the firm is making progress on associates, spokeswoman Leslie Shribman said.

Consulting firm Accenture has 80 Black managing directors, compared with the 31 it had in 2015, said Jack Azagury, senior managing director and market unit leader for the Northeast.

Accenture, Citigroup, Nike and other companies are publishing data on the diversity of their workforce—which allows for public accountability.

Accenture, which ranked first in a list of 100 firms with strong diversity practices, said it is reworking its efforts in light of the current protests. It said the past month has demonstrated that the firm needs to do more.

"Obviously the past few weeks have been extremely saddening and very tough," Azagury said. "I've sat through in the last weeks probably 12 hours of calls, listening to our employees."

Accenture, which has a location in Manhattan, plans to add racism training to its diversity programming, on top of the unconscious-bias training it already holds.

Firms needs to confront racism head-on, Azagury said.

"Some of it is unconscious bias, and some of it is racism," he said. "And we need to call it what it is."

In September the firm plans to unveil a new goal for Black and Latino representation in its ranks by 2025.

"One of the reasons we are going to set goals for 2025 is we are now accountable. We are now in the public eye. We can hold ourselves accountable," Azagury said. "It's not going to be, 'Let's go at it for a few weeks.' We are in it for the long term."

"I do really believe that some people are sincere about it," Johnson said. "I am cautiously optimistic."

He paused, then said, "Maybe even cautiously pessimistic. We'll be here next year this time, wondering why some of these initiatives didn't work. "